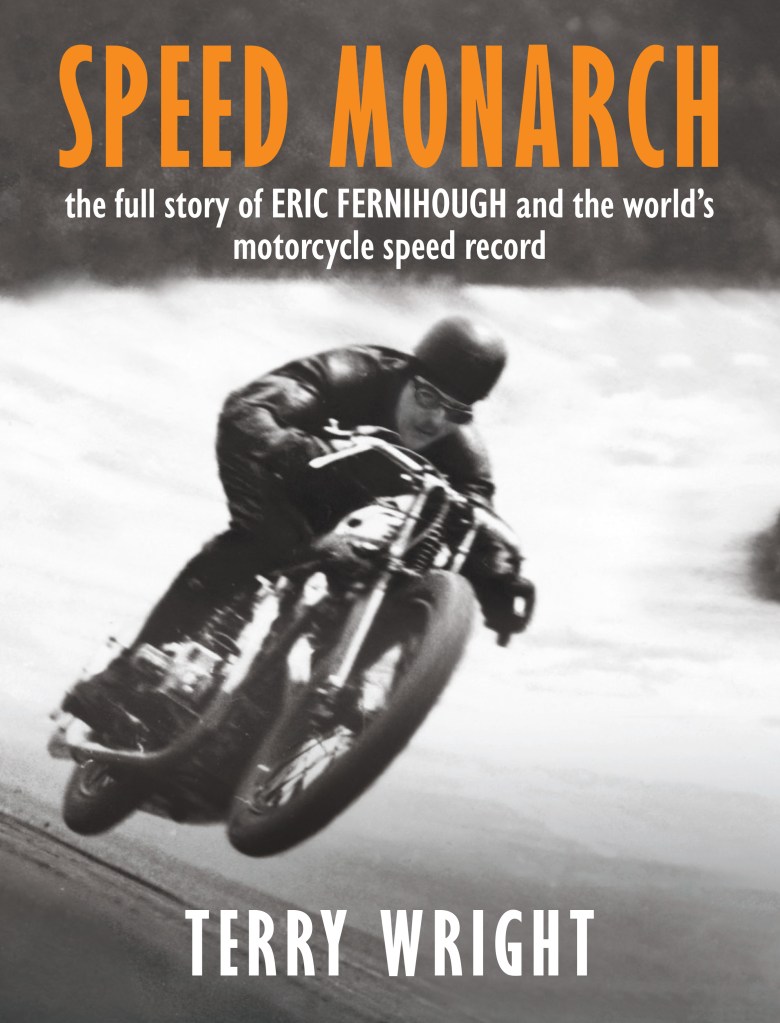

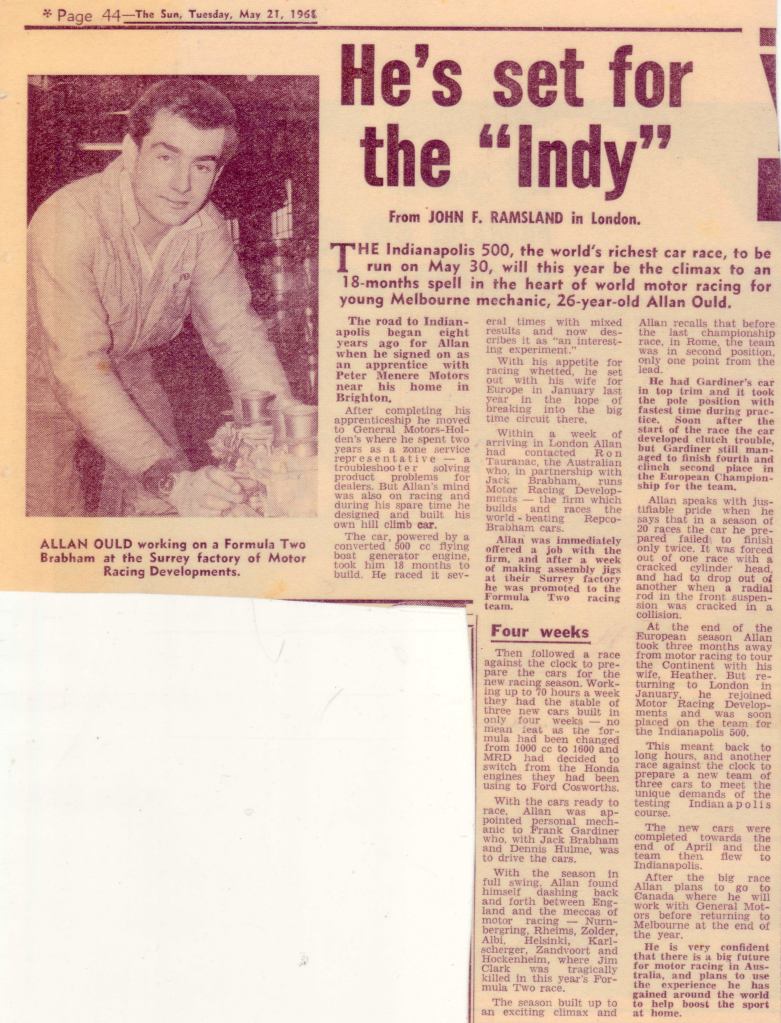

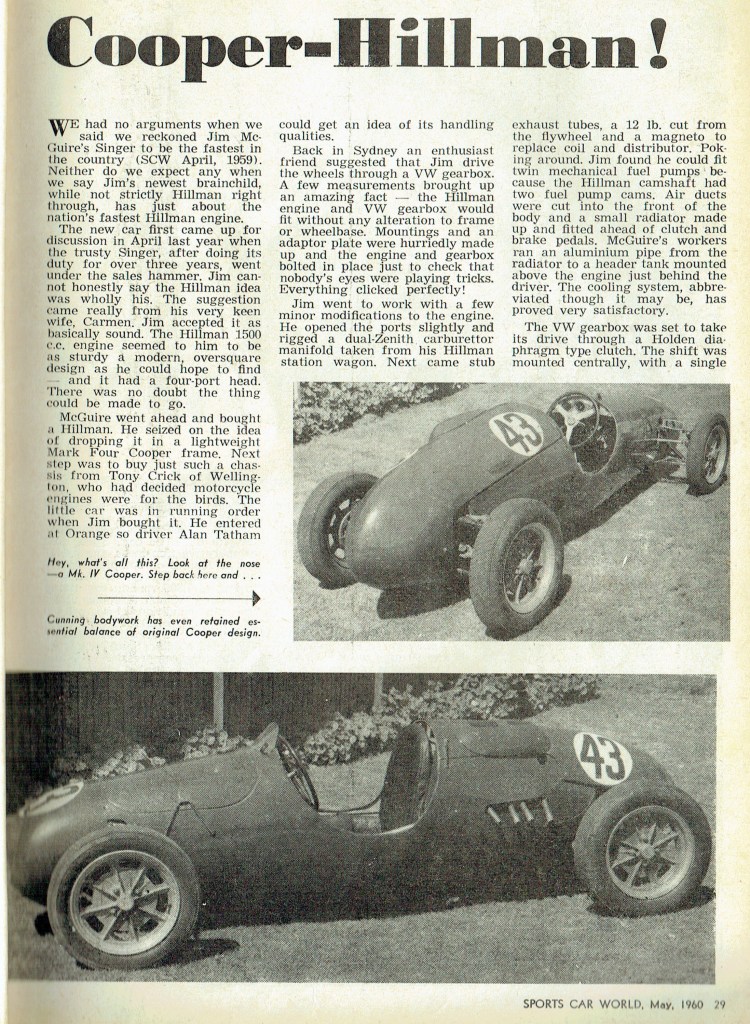

by Garry Simkin

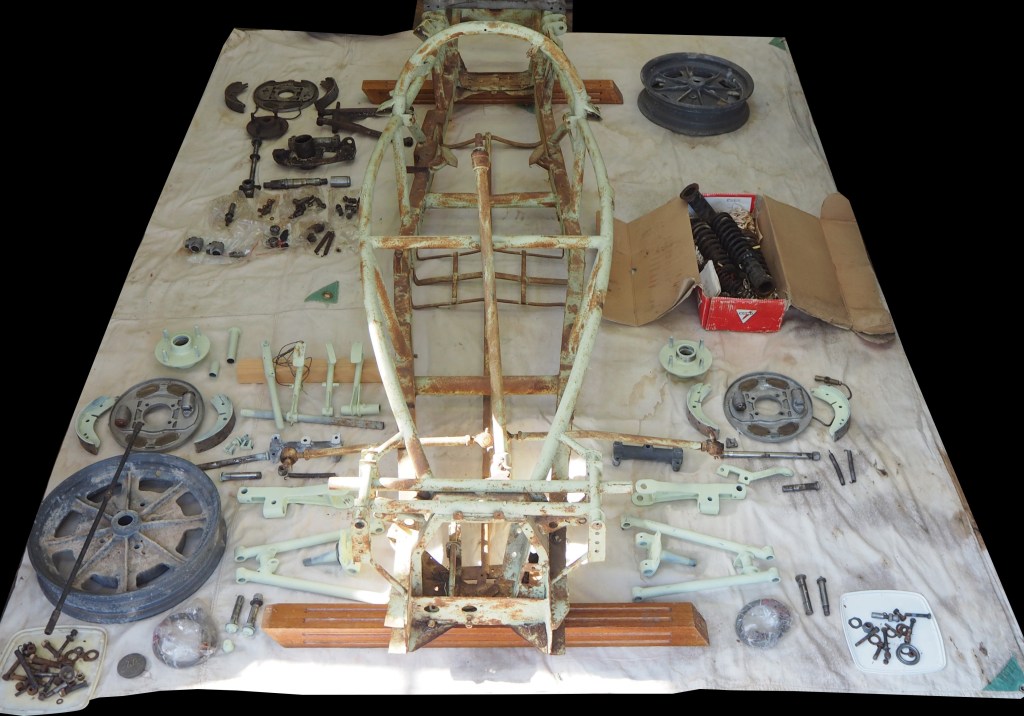

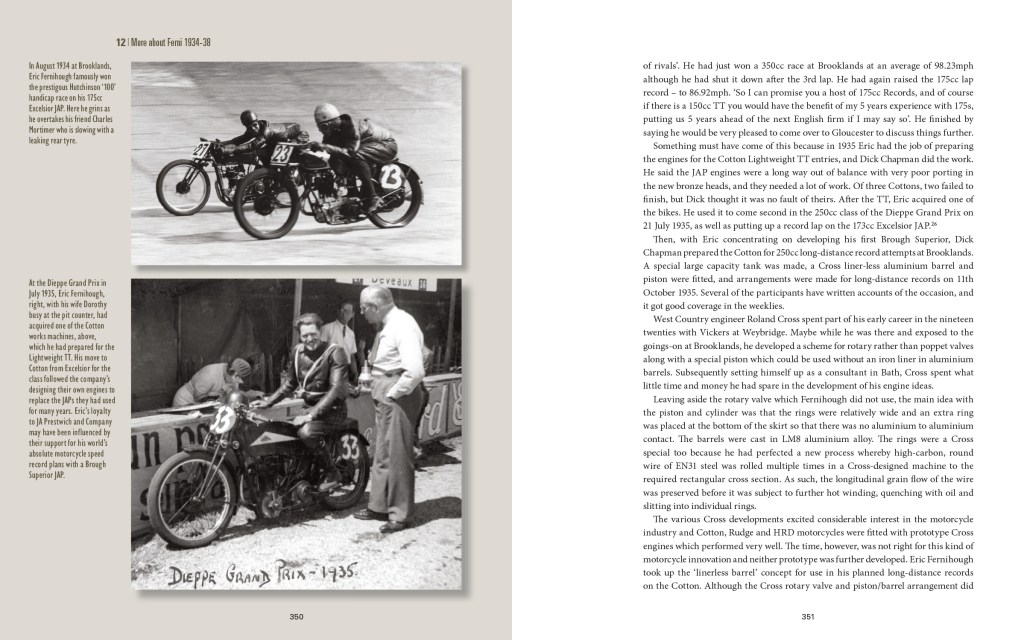

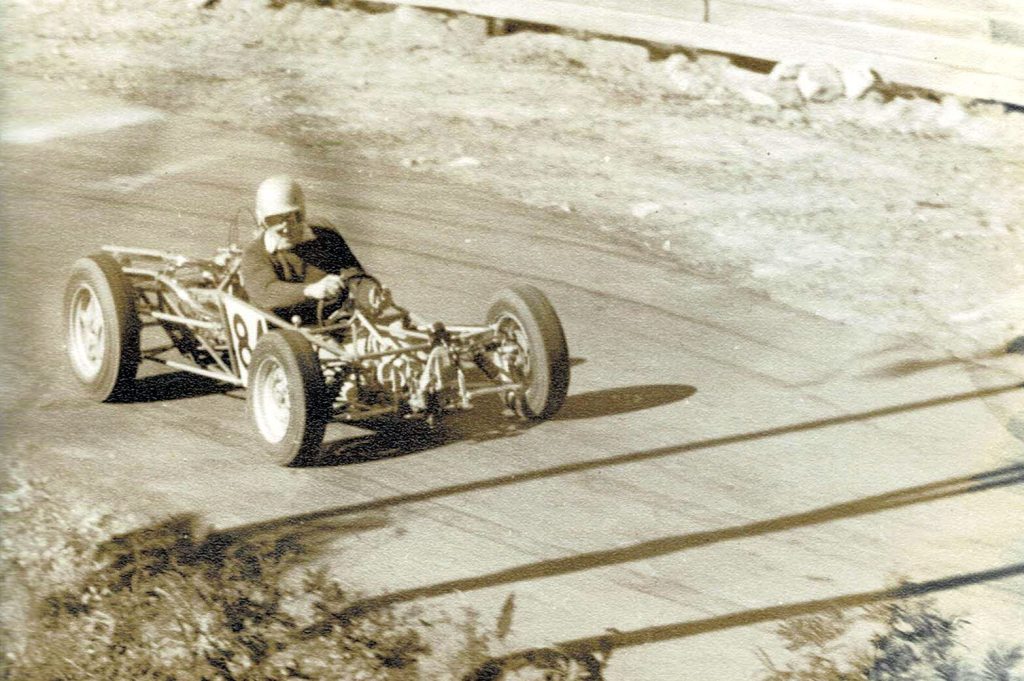

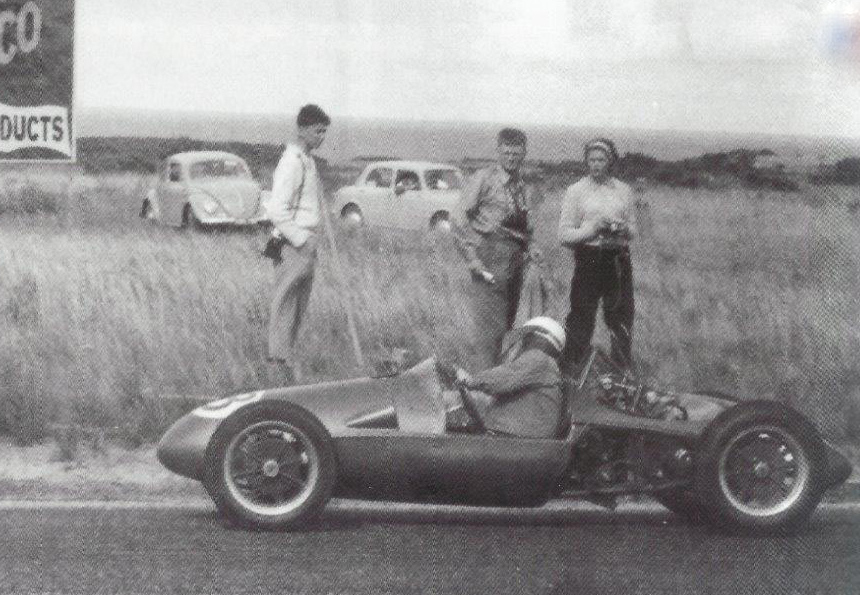

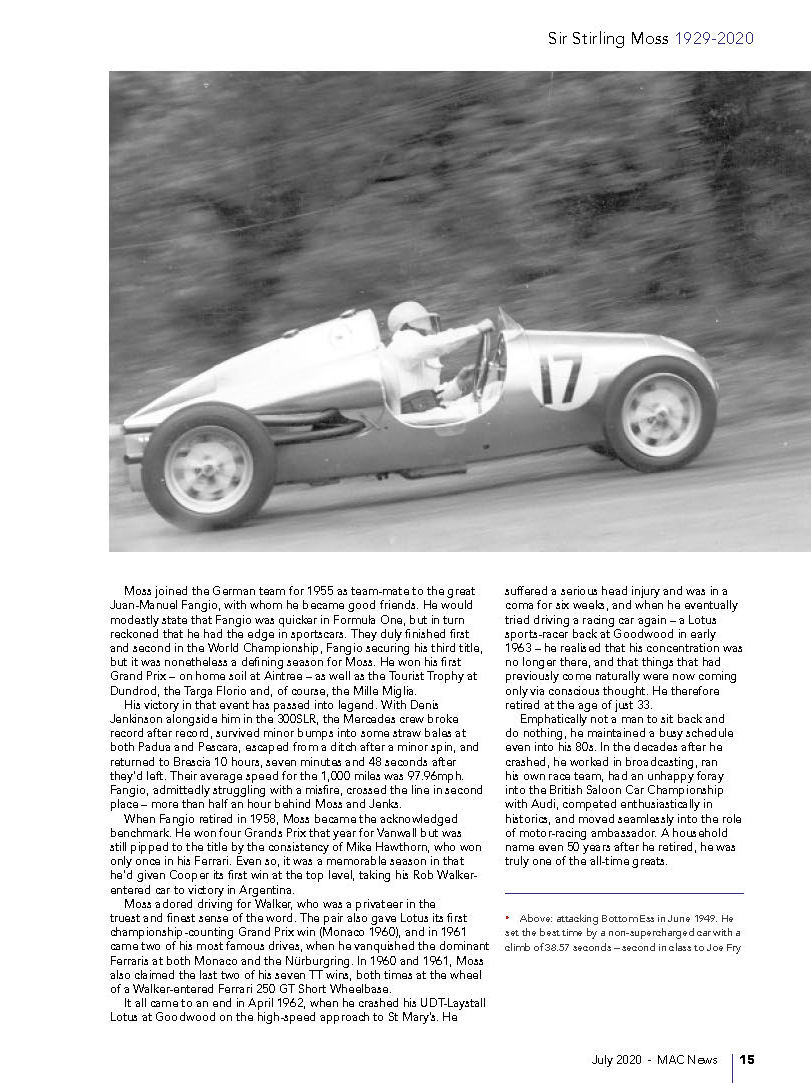

Some air-cooled Coopers have been prominent throughout their lives in Australia and New Zealand, but others remain shrouded in a certain degree of mystery. One such is a big-twin with a 1098cc JAP engine – chassis number 10-48-50 – which was later to be seen with its engine strewn across the paddock at Bathurst in 1957. Here it is, a sad sight, but more on that later.

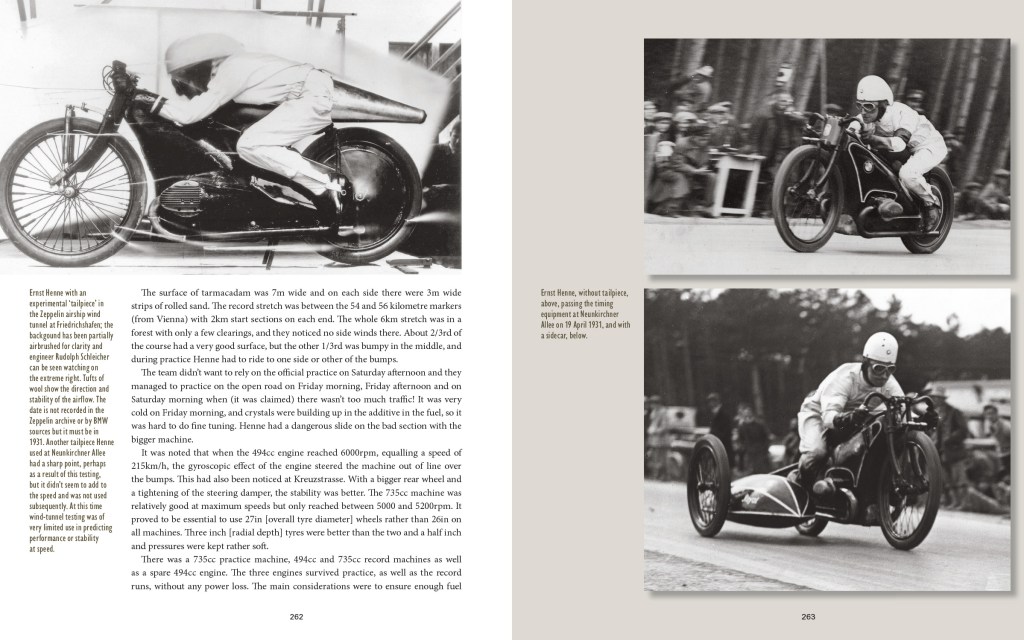

Strewn across the paddock at Bathurst Easter 1957 or 1958

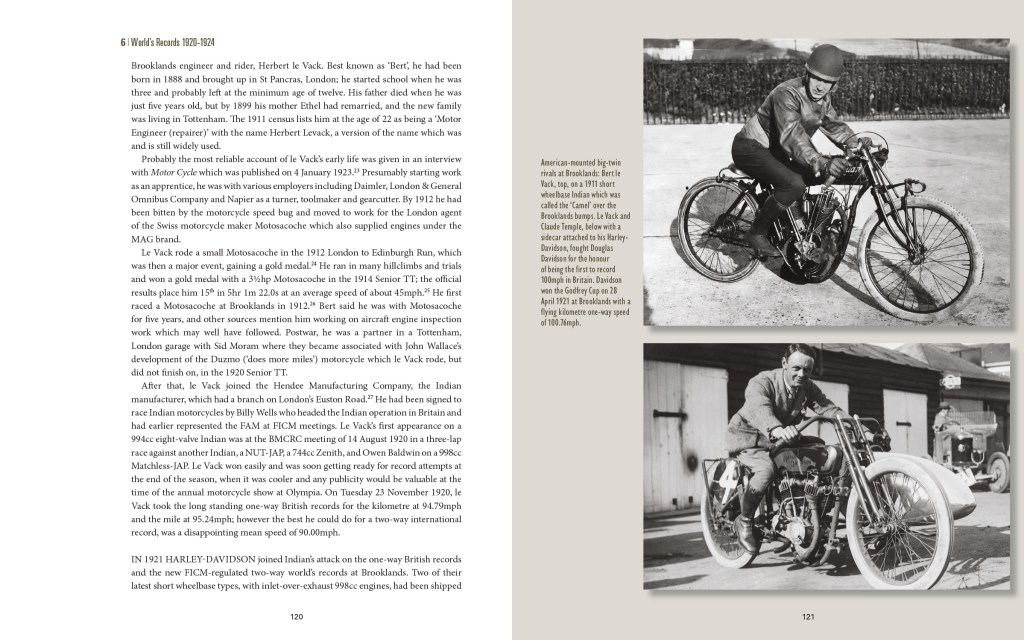

There are no reports of 10-48-50 being first seen in Australia, so Sydney’s John Nind seems to have taken delivery of his new car in New Zealand. Perhaps the car had been ordered by a local customer and was shipped to New Zealand but then Nind took over the order? Maybe he just couldn’t wait for an early season start so had the car delivered there? What we do know is that after a sprint the previous weekend, his first race start was at Wigram airfield near Christchurch on 31 March 1951 for the premier event, the Lady Wigram Trophy race. With a brand new car, what could go wrong?

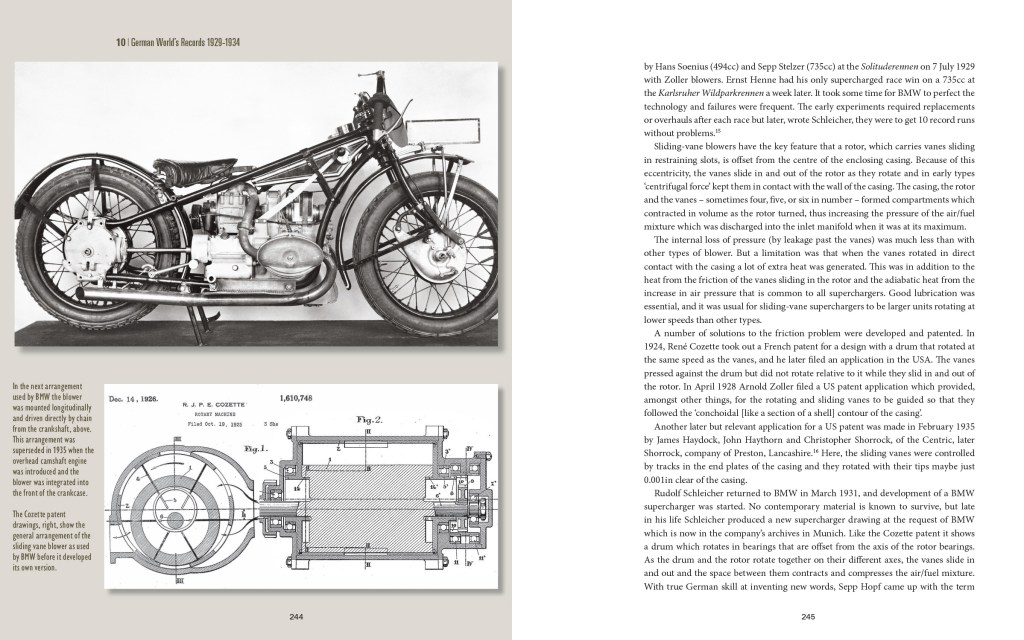

John Nind makes a good start from the second row of the grid in the Lady Wigram Trophy race 31 March 1951

Despite qualifying fifth-fastest and leading initially, Nind completed less than one lap in wet conditions before an accident sidelined him. He had entered for the Easter Bathurst meeting but it appears that delays in getting the car back across the Tasman Sea, plus possible accident repairs, made him a non-starter.

According to John Medley’s monumental history, Bathurst:Cradle of Australian Motor Racing, Nind was next entered for the Bathurst meeting of October 1951 and initially led the six-lap handicap race before retiring; the race was won by Alf Barrett in the author’s Cooper Vincent 10-41-50.

Perhaps not being all that Nind had expected it to be, the car was then advertised for sale in Australian Motor Sport in December 1951 as Cooper “1,100” in almost new condition, under 100 miles competition. Spare wheels, tyres and tubes unused. At reasonable reduction on new cost. John Nind, 38 Pemberton St; Strathfield, New South Wales UM8086

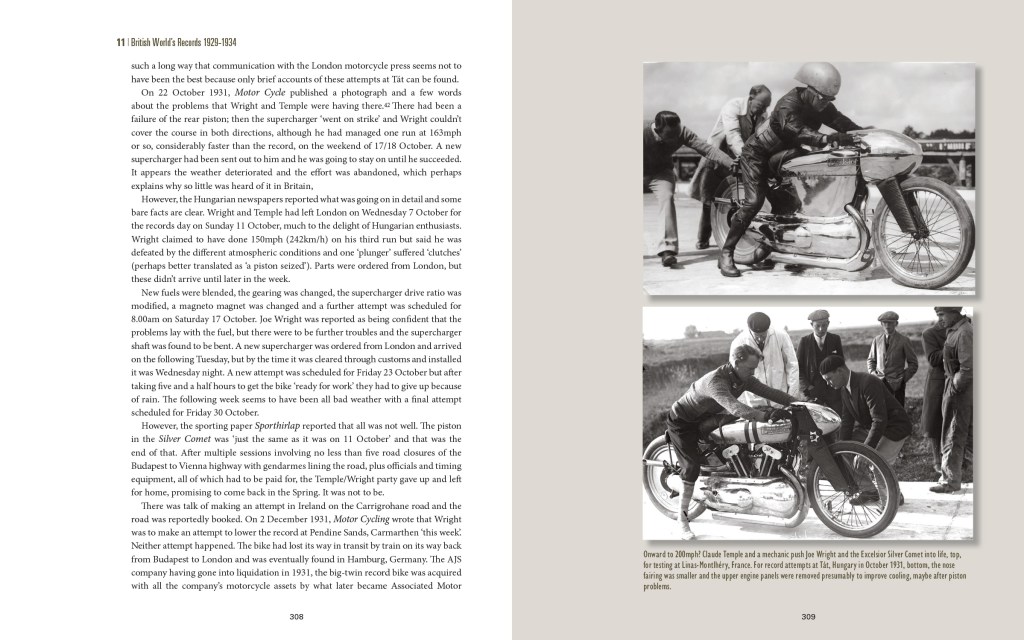

So the Cooper went to Ash Marshall of Sydney who was third in a Redex handicap race at Gnoo Blas instead of Bathurst as was usual, at Easter 1953. Only motorcycles raced at Mt Panorama that year because the Australian Sporting Car Club had fallen out with the authorities and shifted its meeting to Orange. Eventually the Australian Racing Drivers Club took up the challenge of running car races at Bathurst and has done so ever since.

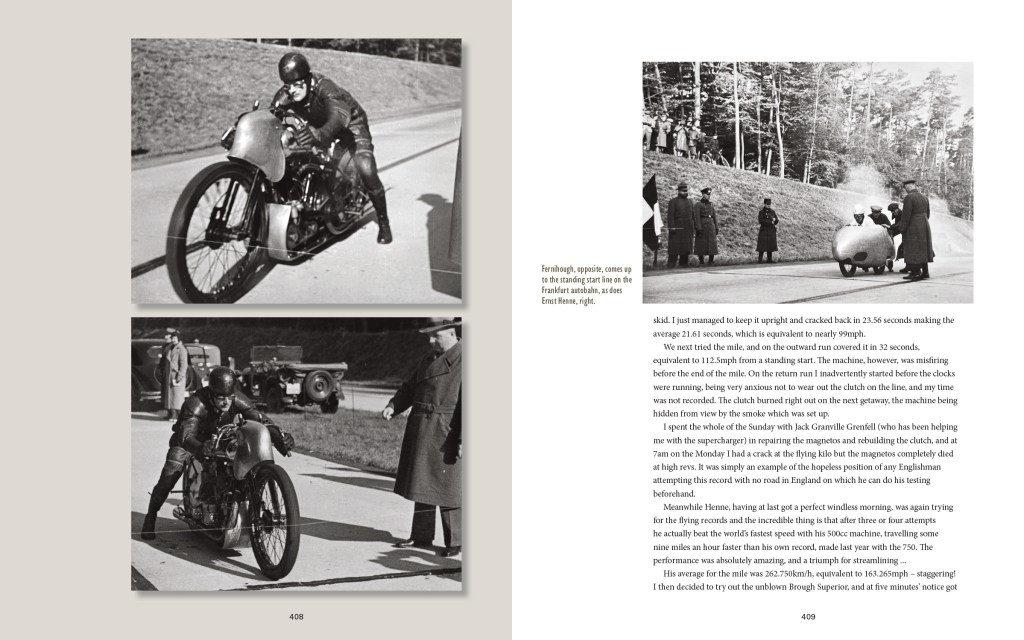

Ash Marshall, right, at Easter1953 alongside Dick Cobden in Mk5-L9-51

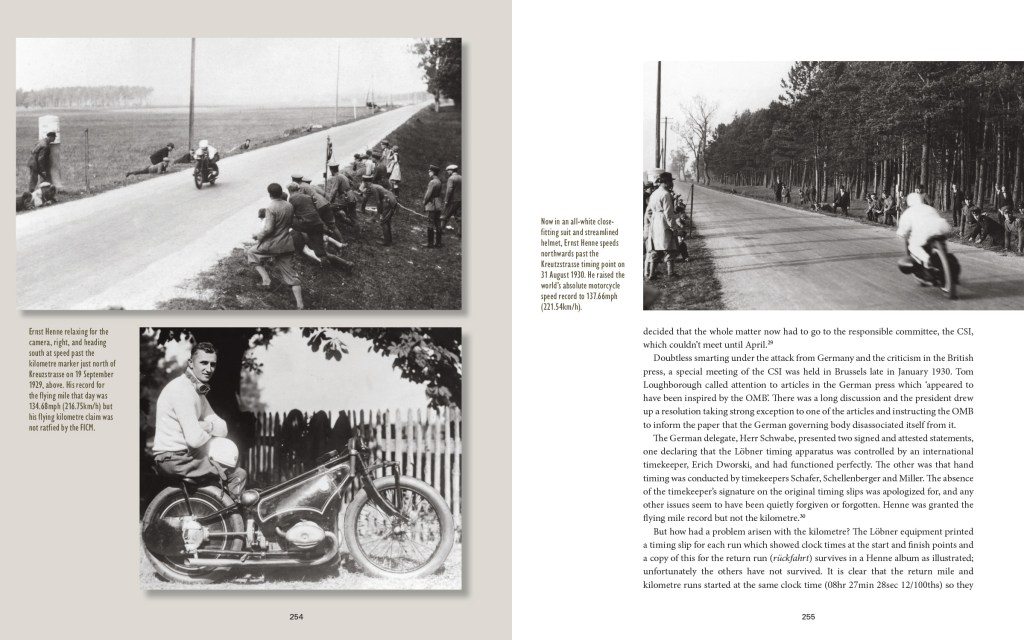

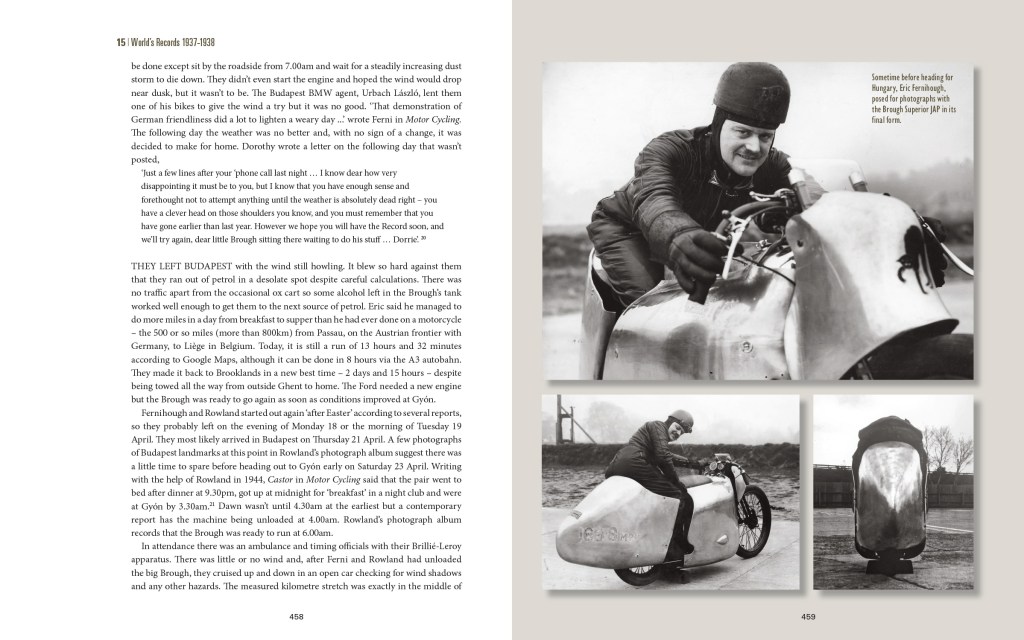

Then the Cooper was sold to Newcastle’s Gordon Greig who was listed only as a reserve for the 18th Australian Grand Prix at Albert Park in 1953 and did not start in the race. Jim Madsen was the next owner, and it is his name on several photos we have of what is now a dark-coloured car. This is seen below at an unidentified Mt Druitt meeting but I am fairly certain from the helmet and other features that the driver is the next owner, the known-to-be-diminutive ex-motorcycle racer Ron Williams.

Ron Williams, probably, in Cooper 10-48-50 at Mt Druitt, date unknown

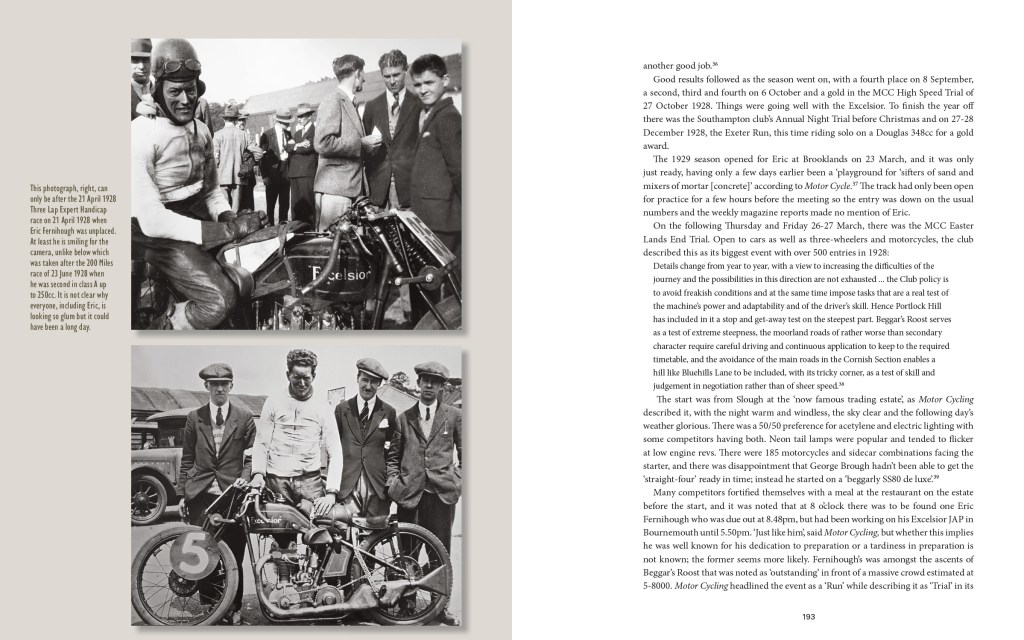

Ron entered the car for the Bathurst meeting at Easter 1957, and finished second in a closely fought three-lap scratch race just behind Frank Gardner’s C-type Jaguar, which must have taken some doing. He was just ahead of Bill Reynolds in his John Crouch Motors entered 996cc 8/80 JAP engined Cooper.

Either at this meeting, or maybe Easter 1958, the car had some massive engine trouble, as shown in the opening picture which graphically illustrates the sad truth about the big-twin Coopers’ reliability over longer distances. Bathurst, which this photo is assumed to be at, was really too much for them.

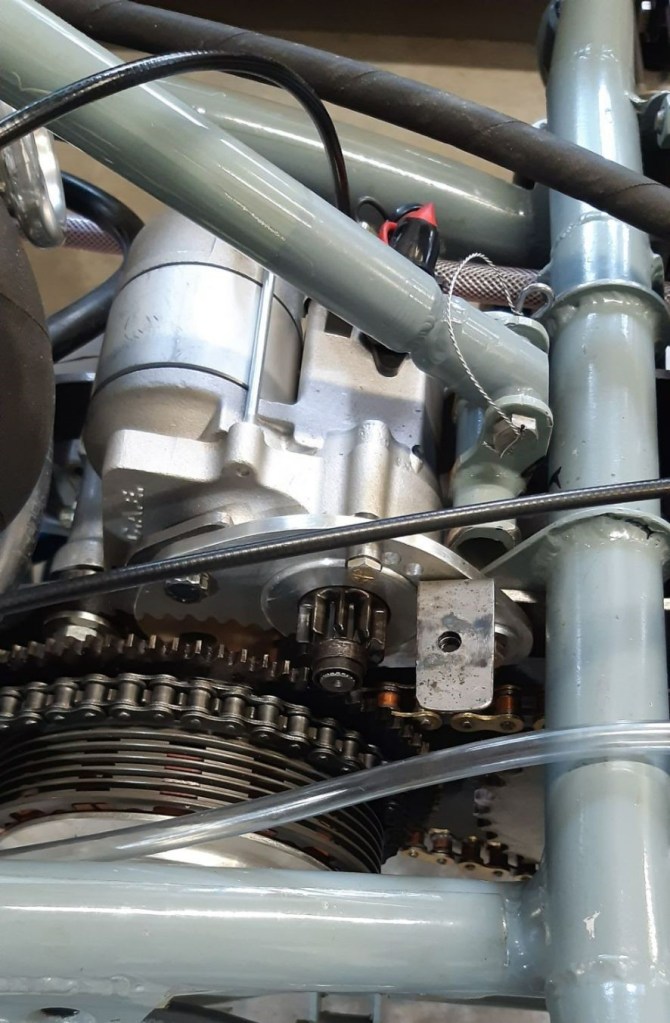

Moving on, the next owner was Phil Boot, also of Sydney. Victorian John Harnett told Loose Fillings some years ago that he recalls going to Boot’s place to buy the car for Graeme Keilerup. He mentioned selling the JAP engine to Tasmanian Dave Powell Snr who, with his son Dave Powell Jnr, did quite a lot of racing with various Cooper JAPs on the Apple Isle.

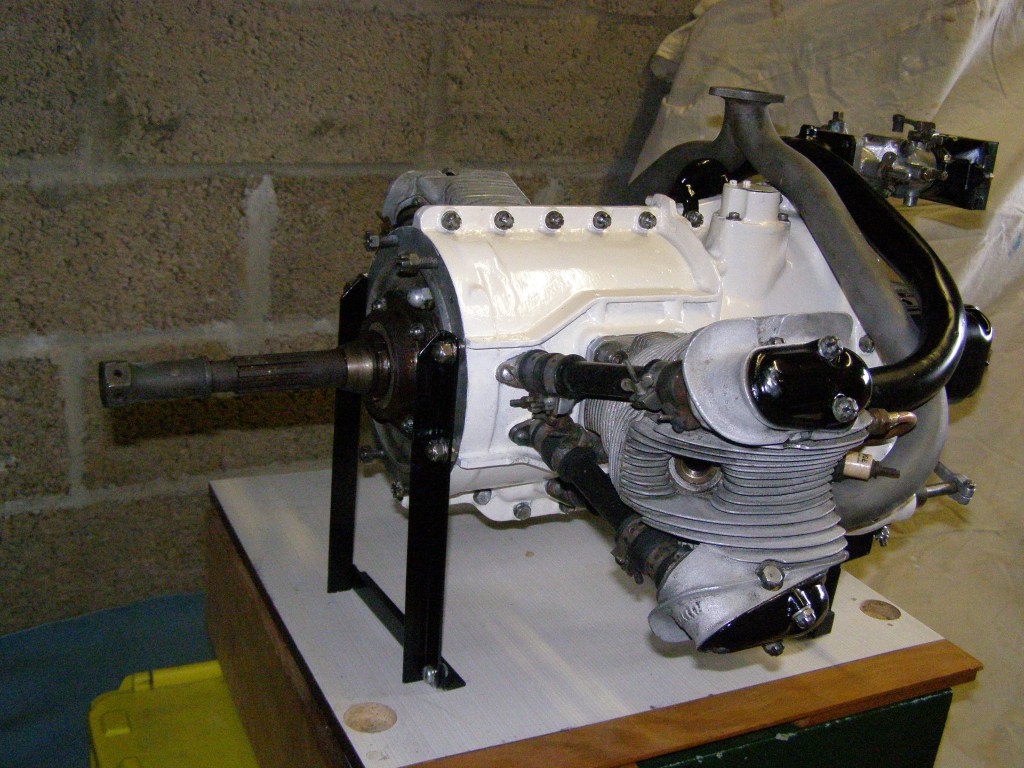

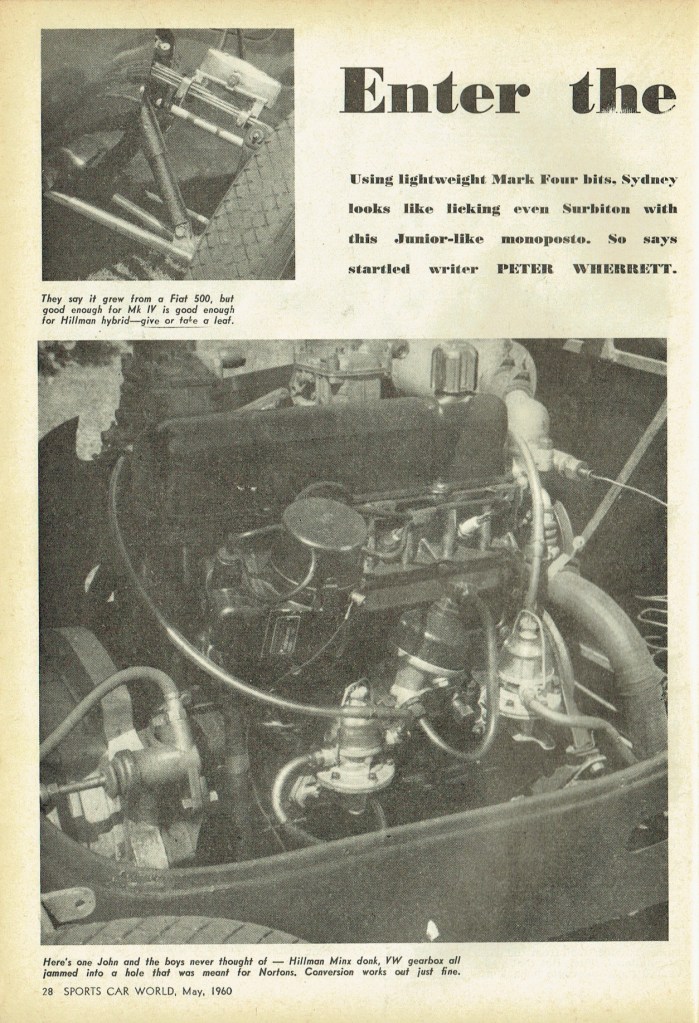

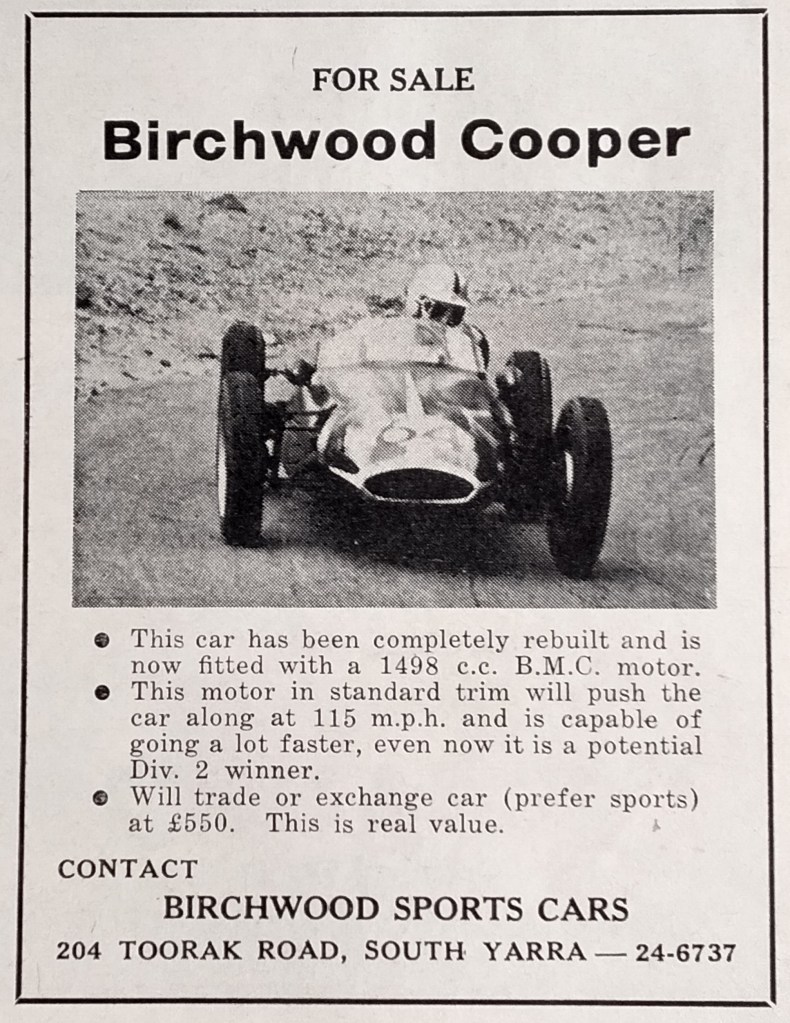

In place of the JAP there was then installed a 1098cc Coventry Climax engine, a project started by Hartnett but later completed by someone else; it was known as the JHM Climax before becoming the Birchwood Cooper.

With a BMC 1498cc engine the car then became the Birchwood Cooper

Fast forward some years and John Bodinnar acquired the car as well as Cooper 10-32-49 before both moved on to ACT vintage car enthusiast John Prentice.

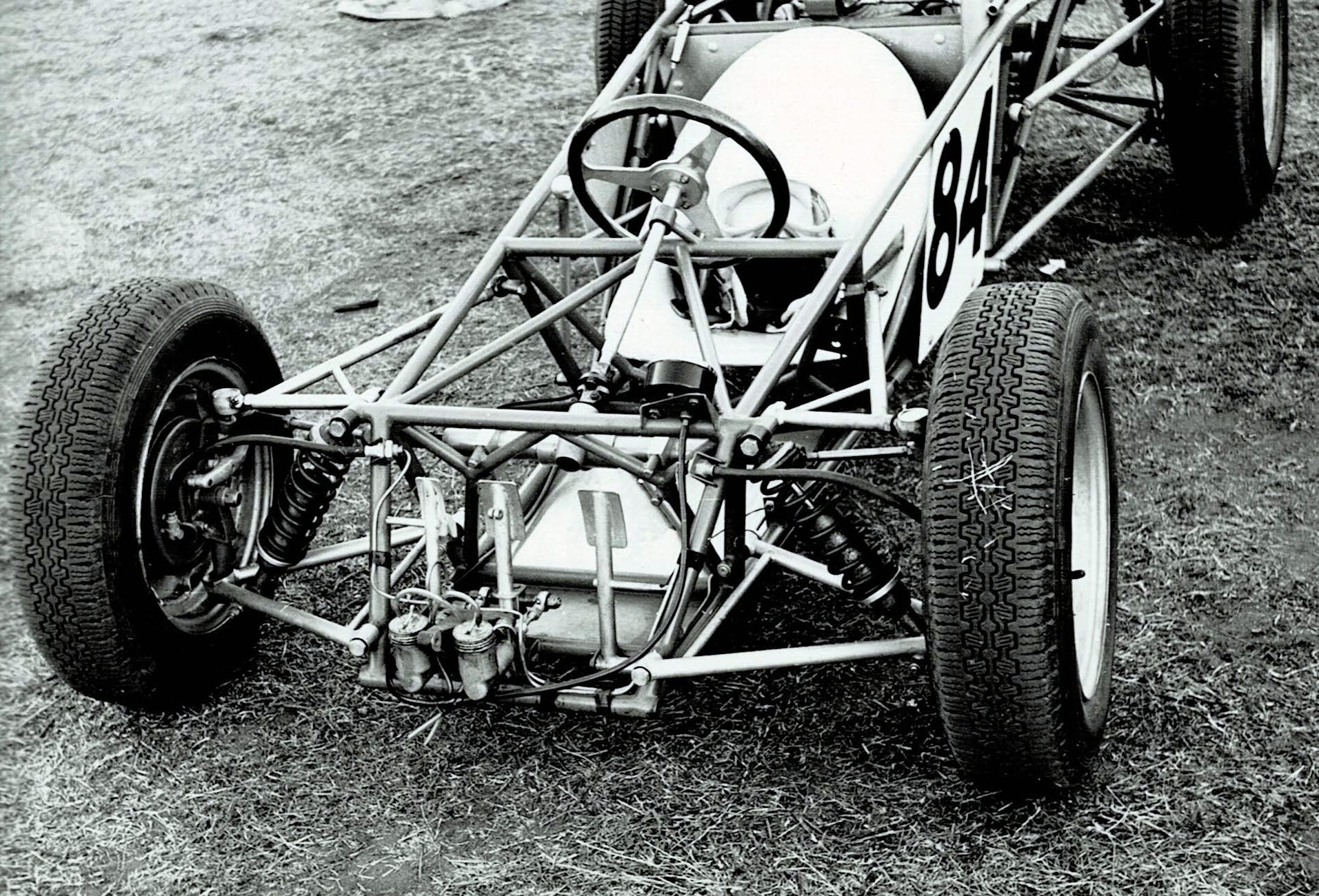

Current photos of the remains, below, show the chassis has been seriously modified over time. The lower part of the early ladder chassis has been retained but the hoops of 1/2 x 3/16” flat steel have been removed and upper tubes as in a Mk8 or later Coopers have been welded on. A lot of work is needed to restore it to its former glory but it is all do-able with the right skills and effort. John also has the Birchwood Cooper body panels.

With thanks to Stephen Dalton for his help.