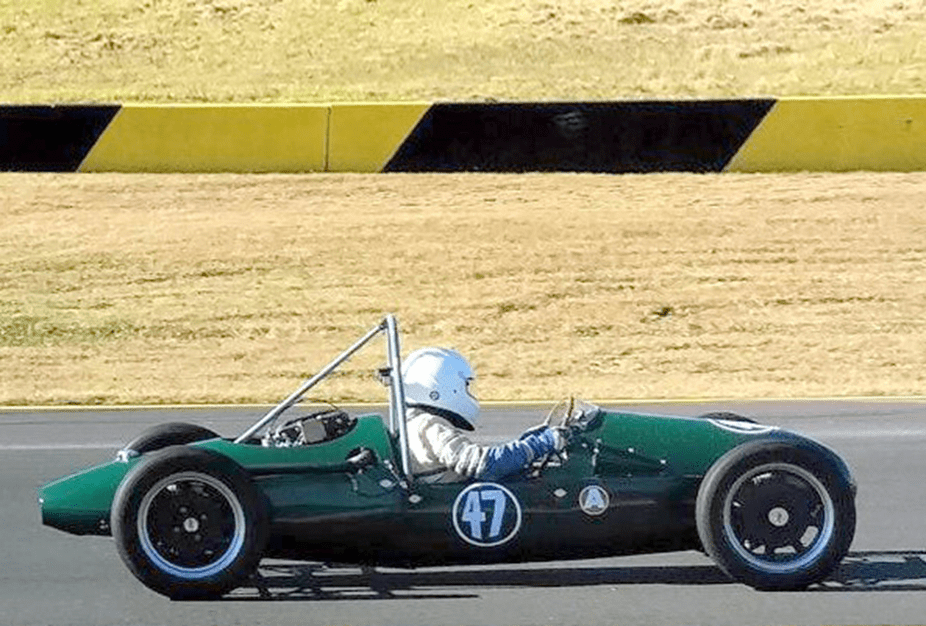

The following abbreviated version of an article by the great Brooklands tuner Robin Jackson recently surfaced in a tidy-up of founding editor Graham Howard’s Loose Fillings papers. The article first appeared in Autosport in 1954. Garry Simkin’s commissioning of a new Norton engine made by Charlie Banyard-Smith in his restored Mark 9 Cooper (photo below by David Williamson) seemed like a good excuse to give its wise words a fresh airing.

Garry Simkin in his Mk9 Cooper at Eastern Creek

Some years ago, it was decided to investigate the possibilities of improving the performance of the standard Norton engine specifically with a view to its application to 500 c.c. car racing.

The first task was to obtain a clear picture of the standard engine, and to ascertain, if possible, what were the factors limiting its performance and what possibilities there were of making improvements. Essential, therefore, was a test set-up which would reproduce accurate and repeatable data and which would allow the running of the engine on an open exhaust pipe fitted with a megaphone, under conditions that as near as possible simulated those that were met in the 500cc car.

A programme of investigation on the standard Norton engine was put under way with a view to ascertaining where possibilities lay for improving its performance. At this point it might be as well to digress and point out that the most suitable shape of power curve for a motorcycle engine is not necessarily the best for a 500cc car. The average racing motorcycle has as much horse power as the rider can use at the bottom end of its power range; the general tendency, therefore, when developing a motor-cycle engine, is to seek for higher powers at higher rpm.

In the case of the 500cc car, however, the driver is able to use all power that can be obtained from the engine over the lower portion of the power curve, and as practically all circuits demand good acceleration rather than sheer maximum speed, the essential requirement for a 500 c.c. car is that one should produce a very good power output throughout the entire range of the engine. It is very rarely, if ever, that power at the top of the scale, when bought at the expense of the bottom end, produces faster lap times on the actual circuit.

When testing at Goodwood we decided to shorten the exhaust pipe by 2 ins. (using the same standard megaphone) and gained an increase in rpm, down Lavant straight of 250 to 300 and a drop of 200rpm approaching St. Marys’. The lap times increased by 1/2 sec, showing that extra power at the top end, when bought at the expense of the bottom end, does not improve lap times but, in fact, slows them.

As it was a necessary requirement from a commercial angle that the standard Manx Norton cambox had to be used with the cylinder head, one was, of necessity. limited as to the alterations one could make to the head, since obviously the valve angle and valve positions had to remain basically the same as the standard engine.

It was accordingly decided, after examining the test data of the standard unit, that the best hope of obtaining an improvement in the performance of the engine was to try and improve its filling; accordingly, the inlet port was moved round from the standard Norton position of 15 degrees to the front-rear centre line on the front-rear centre line and the exhaust port was also moved on to this line. In place of the normal exhaust ring nut (which comes loose and the thread strips) a short length of steel tube was cast into the head, over which the exhaust pipe slides, thereby providing a slip-joint.

The new Jackson head – are there any in use now?

At the same time as this was done the cylinder head was stiffened considerably, as it had been found that a certain amount of distortion of the head on the standard engine took place with the resultant nitromethane was used. The possible alterations to the shape of the inlet port were to a large extent governed by the existing valve angle. A considerable amount of development work was done on the shape of the port on an airflow rig which consisted of a Wade supercharger, the airflow on the inlet side of which was measured by a British Standards sharp edge orifice. The air from the outlet of the supercharger was led through suitable ducting to the inlet port, a static tapping being taken off the ducting to a manometer, which read the pressure differential across the inlet port and the valve seat.

Cross-sectional drawing showing the best shape that could be achieved for the inlet port

The airflow at various valve openings was plotted against the manometer readings and by this means the shape of the port shown above was developed. A cylinder head was then made and bench-tested, having a sparking plug in the same position as the standard Norton engine. This head showed a small improvement in power over the standard head, but there was evidence of detonation at the maximum B.M.E.P. condition which occurred around 5,000rpm, which was definitely more pronounced than on the standard Norton head.

The engine was run under these conditions and a careful examination was made of the carbon deposit on the cylinder head and piston. Evidence showed that detonation was taking place adjacent to the edge of the inlet valve seating on the opposite side of the head to that in which the standard plug was fitted. It was accordingly decided to introduce a second sparking plug in this position.

The question of providing two simultaneous sparks then had to be solved. Initially a B.T.H. magneto was used, but it was found that this instrument did not produce the requisite voltage to operate the sparking plugs under the maximum B.M.E.P. conditions met with on the engine. Two Lucas twin spark magnetos were then located which had been developed in the pre-war years and these were reconditioned by Joseph Lucas Ltd.

Power and rpm graphs for the Jackson head.

Running with the Lucas twin-spark magnetos, an improvement in performance was obtained and the tendency for the engine to detonate was slightly reduced. It was found that whereas with single ignition the required timing was 34/35 degrees before TDC, with dual ignition the correct timing was 28/29 degrees before TDC.

An examination of the cylinder head showed, however, that there was still evidence of detonation around the edge of the exhaust valve seat immediately opposite the plug which had been fitted adjacent to the inlet valve: accordingly, the head was drilled and tapped to accommodate a second 10mm sparking plug. Further running using two 10 mm. sparking plugs was carried out and the tendency for detonation was found to have more or less completely disappeared. it is of interest to note on the latest standard square Norton engine, that burning due to detonation takes place in exactly the same location as we found when we used the standard Norton plug position on our head.

Whereas previously the power output of the engine reached the peak around 6,500r.p.m. and then fell off, the power output now carried on beyond the peak without any falling off up to 7,000 rpm The engine also showed better power around the satisfactory minimum rpm, of 4,400, which was attributed to the better combustion conditions obtained with dual ignition and the better mixing of the fuel with the air. Prior to the introduction of dual ignition, the piston crown was kept close to the cylinder head round its circumference. Due to the position of the sparking plugs, which are very near to the cylinder head face, a piston of this type would have produced partial masking of the plugs; the piston was accordingly chamfered as shown at 45 degrees, with the result that with adequate valve to piston clearance, which is reckoned to be 6 mm.at TDC, a compression ratio of the order of 12 1/4 to 12 1/2 was obtained, which appeared to be the optimum ratio.

All 500 c.c. car engines are run on virtually pure methanol, with the result that whereas the fuel consumption on petrol is of the order, of 730 pints [414 litres] per bhp hour, on alcohol it is [of the order of double that]. The carburettor therefore has to mix a very much larger volume of liquid with the air than in the case when petrol is used, and, broadly speaking, the carburettor delivers a mixture in the case of petrol which is akin to a relatively fine mist-while in the case of alcohol this approximates much nearer to a thunderstorm.

To summarise the position to date, it would appear that the result of fitting this type of cylinder head has been two-fold:

(1) To raise the actual power of the engine throughout the range; and

(2) To extend the range of the engine over which useful power is obtained from 6,500 rpm to 7,000 rpm[T+RW1] .

Sorry about the hyphenation – not our doing

LikeLike

Very interesting article and have shared with fellow manx norton enthusiasts.

LikeLike

Nice read , very interesting work done too !

LikeLike